Rosin stood at the top of the hill a dozen yards off the trail.

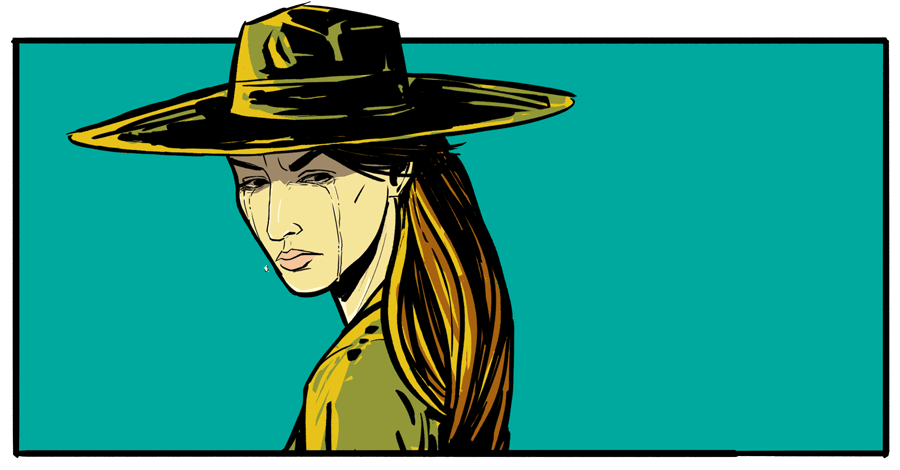

“Rosin! What the hell? What are you doing?” I shouted, as I ran toward her. She looked at me and I saw her face was streaked with tears.

“Rosin, Mel—they’re—” I stuttered, unable to get the words out.

“I know,” she said. Then silence.

“You know? What?!” I was beside myself with grief and terror and could not understand why Rosin was doing nothing. “You know what happened to Mel? Then why are you just standing there? It’s going to happen to them, too!”

The world around me might be going mad, but this conversation seemed to be happening in slow motion.

“I made a promise to myself,” she said after a long pause. “I refuse to control people or keep them from the pain of their choices.”

“But Mel was killed by that needwell—how can you just stand here and let these people destroy themselves?”

“Mel isn’t dead; they’re not really even gone,” she said.

“What?”

“Mel will have other chances to return here—just not soon. It will take a long time to realize they’ve even given themselves over entirely to the needwell,” she said. “And then they’ll need to recover from the burnout. I expect they’ll be back one day. It’s not unusual for people to cycle through this land a few times. Everyone must make their own choices—it hurts so badly to watch.”

Rosin wiped her eyes.

“Deep down, we all prefer comfort and safety and avoidance of pain,” Rosin said. “People will do anything to keep from facing their own souls. Filling a needwell is much less terrifying than following the call of your wildling. Sure, cage it, dominate it, use it—but absolutely don’t follow its wildness into dangerous and unknown territory. Certainly don’t follow it into creating and exploring an entirely new world. That’s scary stuff! So much easier to fill a needwell! And the needwell will make you feel great about it when you do.”

“But those needs are real,” I said, still processing everything that’s happened. “There’s very real decay there—and they are bringing healing.”

“Are they really?” Rosin looked at me. “Some people, when confronted with the world’s problems, think: ‘I know, I’ll solve this and then I’ll be rich and famous!’ Now we have more problems.”

I remembered the decay rapidly spreading in multiple spots outside of Mel’s needwell.

“The needwell. You called it the world, right?” she said.

“That’s what it called itself to me.”

“You’ll note it won’t call itself the earth. The earth—nature—is not like that. Death and decay is a natural part of the cycle of life—and not just physical death, but the hundreds of tiny deaths and rebirths that happen throughout our individual lives. Some things need to die so that new things can live. And we must stop resuscitating things which are asking to die—there are many things we choose to keep alive only to satisfy our own egos.”

“The needwell preys on our fear of pain and loss, but it’s pain and loss that shape us and help us become who we must be,” she said. “Without decay, we wouldn’t have rich soil that sustains new life. The only way to make the world whole is to become whole ourselves—and to create something new out of that wholeness.”

“But why won’t you just try to stop them?” I asked. “Why won’t you tell them all of this?”

"Do you know Michael’s story?” Rosin asked. I shook my head no.

“You’ve met him—he’s generous, selfless, compassionate,” she said. “He loves to serve people. When I first met him nine years ago, he was the type of person who would do anything for anyone who asked. He became a very dear friend to me. And then I lost him—twice.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“Just like Mel, he was drawn to the needwell. He set aside pursuing his wildling because he just felt compelled to do what he could to help—the pull was too strong. At a swamp three miles downstream from the camp, he succumbed to a needwell. I pled with him. I did everything. I tried so hard to stop him, but I couldn’t do it. I hoped he’d be back one day, and I vowed that if he did come back I would do everything I could to keep him from succumbing to the needwell’s siren call.”

“How long did it take him to come back?”

“Two long and lonely years,” Rosin said. “I missed him every day. I missed playing music with him, missed his passion for coffee, his goofy love of Zelda. And then, one day, he was back.”

“Did Michael remember you?”

“No, and that’s really the hardest part. When people come back, there is a deep part of them that remembers—like waking from a half-remembered dream. The feelings are still there, the pain, the joy, glimpses of images from memory, but nothing clear, concrete.”

“Man. Did he remember what happened to him?”

“He seemed to in a very hazy way, but it was like this deep, unresolved pain. He didn’t really know or understand what happened to him, but he had a sense he had been here before and he kept saying he wanted to go explore away from the camp, and talked about waking from dreams about a swamp. Feeling the pain from those dreams, he would ask me repeatedly if I knew anything about the place and what happened there.”

“Did you tell him?” I asked.

“I lied to him. I just tried to keep him away.” Rosin wiped her eyes and took a breath.

“He was so driven to help and to serve,” she said, continuing. “His greatest passion in life was being useful to others. He was obsessed with finding ways he could show his value. We fought a lot about that. ‘The world needs us,’ he would say. ‘The world needs us, Rosin.’ I just fought and pushed against that. I tried so hard to protect him. God, I regret that.”

“One morning, I couldn’t find him,” she said. “I went to his tent and there I saw the line—you’ve seen it before. ‘THE WORLD NEEDS YOU’. I ran out of camp toward the swamp—of course, by this time, natural forces had returned it to its decaying state. By the time I got there, it was a pristine lake rimmed with flowers. And Michael was gone. I had kept him from knowing and seeing the full truth of what he had experienced the first time. I had tried to keep him from feeling the pain. And I was wrong to do that.”

“I had to wait another six years for him to return,” Rosin said. “I promised I’d never again keep people from making their choices or experiencing the pain from them. It is possible to hold on so tightly to someone that we smother their potential and growth with our own fears and insecurities, and through our desire to save them or protect them.”

“Most of us are lucky enough to get multiple passes at pursuing our wildling,” she said. ”I’ve come to believe that even if people do the ’wrong’ thing, if they do it with all of their hearts, they will eventually end up where they need to be. Pain is life’s greatest teacher.”

I walked down the hill slowly in a daze. I had expected to rush there and save everyone—but I was no longer certain that’s what I was supposed to do.

The green patch amidst the blackened woods had grown considerably. Drawing closer, I saw Taylor arguing with Dex. I saw Michael talking compassionately to a group of campers with tears in his eyes. Taylor was in absolute anguish when they caught my eye.

“Where have you been!?” Taylor said, voice cracking.

“I was talking to Rosin. This is awful, I know,” I replied.

Taylor rushed over and I caught them in a hug.

“This happened to me. Thishappenedtome. Thishappenedtome,” Taylor sobbed into your shoulder. “I was here before, years ago. I remember now. I remember it. Please, please don’t let this happen to me again.” Taylor collapsed in exhaustion from the emotional intensity of it all. I led them to a log to sit down and comforted them for a moment.

I surveyed what was unfolding before us. Scattered in and among trees and embedded in various places in the landscape were dozens of our fellow campers—each smiling and happy, overjoyed at what they were creating and how good it felt to be needed and to make such a positive impact. Each of them with their wildling, caged and suffering.

It was a painful sight to behold. The next few hours were excruciating. Taylor and I shared passionately with everyone what we had seen happen to Mel. Michael told and retold his story. I pleaded. We all begged. I showed them what’s happening to their wildlings—and what will happen to them.

But the voice of the needwell was compelling. My ways, Rosin’s ways, Michael’s ways, were selfish, it says. We’re withholding ourselves from giving to fill the needs of the world.

“The world needs us!” Dex shouted at you. “The world needs you, too—you’re just too self-centered to do anything.”

“There’s only one of me, Dex,” I said. “And I’ve seen the world I’m called to help create and explore. I’m absolutely terrified to do it, but I can’t destroy my wildling and give myself to something that doesn’t come from who I am.”

Some people listened to us. They stepped out of the needwell, and released their wildling. Most didn’t. One by one, we saw them encounter the same fate as Mel: their wildlings howled in pain one last time and each of our fellow campers disappeared.

In the aftermath, the small group that remained walked back to camp, dejectedly. I saw Michael talking to one group as they headed back, trying to give them hope and peace.

I thought about Mel and finally let myself cry. Someone approached from behind and put their hand on my back. It was Rosin.

“Rosin—will I see Mel again?” I asked with heavy heart.

“Probably—someday. I know you miss Mel deeply,” Rosin said. “Don’t forget not to hold on too tightly to someone who’s gone—you’ll miss the one who’s right here.”

She nodded toward Taylor.

My friend.